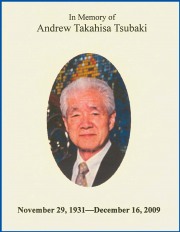

My Andrew Tsubaki Story

Many people shared their personal recollections of Andrew Tsubaki at the memorial service in Lawrence, Kansas on 20 December 2009. For me, the two most moving testimonials came from his sons.

Philip, the younger son who lives in Campinas, Brazil, said his father left Japan for North America in 1957, at the age of 26, his character and personality already formed as a young Japanese male from that period—strict, stern, austere, demanding, undemonstrative, unemotional. Philip confessed that he was surprised, and ultimately comforted by, the many email messages which poured in from his father’s former students—one in particular, which said that “the sensei always had hugs for everyone.”

Arthur, the older son who lives in Rockford, Illinois, spoke of his father’s love of travel, and how he took Lily and the boys with him whenever he could. But, Arthur said, they rarely actually travelled together, because his father always departed a day or two earlier, to make sure all the arrangements and accommodations were satisfactory. Having paved the way, he would then meet the family at the airport upon their arrival, and that’s how all their trips began. Arthur ended the reminiscence by saying this is how he now views the death of his father—that, as is his habit, he has simply preceded them on yet another trip, paving the way for them, and that they will again find him waiting for them at the end of their journey.

Although I thought I would, I was not among those who spoke at Andrew Tsubaki’s memorial service, because I suddenly didn’t quite know how to put my thoughts into words, not after I heard the outpouring of grief and love from his two sons. But now, a couple of days later, my mind a bit clearer, I’d like to share my own Andrew Tsubaki story.

In 1995, Andrew directed the English Alternative Theatre production of Tea by Velina Hasu Houston, a play about five Japanese warbrides trying to live “normal” lives in Junction City, Kansas. As the producer of the show, I had made arrangements to hold our rehearsals in a large studio-like space on the second floor of Liberty Hall in downtown Lawrence. A couple of days before rehearsals began, Andrew asked me if the budget for the production could include the purchase of half a dozen each of the following items—brooms, dustpans, mops, sponges, buckets.

“Yes, of course,” I replied, “but what are they for?”

“The rehearsal space is sacred,” he said. “This place is not as clean as it should be. The actors must clean this place each night before we rehearse.”

And that’s what they did, the five Asian women we had found to play the Japanese warbrides, on their hands and knees each night before rehearsals began, scrubbing and cleaning those wooden floors at Liberty Hall in downtown Lawrence. Needless to say, the EAT production of Tea was wondrous and magical. Andrew Tsubaki would not have had it otherwise.

Although I love the notion that the rehearsal space for a play is sacred, I’ve never dared to ask my actors to do what Andrew Tsubaki demanded of his. Only the sensei could get away with it. I have visions of him now, supervising a choir of angels, all of them on their hands and knees, purifying the heavens, because the final resting place of an artist is, without any doubt, sacred.