June, 2010

Kirby Fields' Forty Days to Forty Plays Interview

OOB Festival (OOB): Tell us a little about your playwriting career. When did you start writing plays? What are some of your proudest accomplishments as a playwright?

Kirby Fields (KF): I was progressing nicely in a fairly typical graduate-school career until I arrived at the University of Kansas and fell in with Paul Lim and English Alternative Theater (EAT). EAT is the only theater company housed within an English department in the country, and it just so happened that I was stationed in an office directly across the hall from them. As I was secluded in my office hunched over whatever I was reading at the time, I heard passionate conversations emanating from Paul’s room. Paul and a fellow playwright talking about their work. I had ended up in Academia kind of by default. I always wanted to write creatively, but when I was younger my enthusiasm far surpassed my abilities.

By the time I was at KU, however, enthusiasm and ability were more closely aligned. EAT seemed like a prime opportunity to do what I had always wanted to do. At first I was too entrenched in my academic pursuits to do anything other than volunteer as a stage manager, but it wasn’t too long before I decided that I wanted to do more for them than just keep track of props. Inspired by EAT’s commitment to producing student work, I decided to finally put down on paper an idea that had brewing in me for a number of years. I wrote my first play over spring break, gave it to Paul the week after, and it was in front of an audience that fall. That was it. I lost my interest in scholarship. Playwriting took over.

OOB: Describe your experience at EAT. How is the approach different for a theatre company that’s based out of an English Department as opposed to a more traditional company? What are some of the advantages to a program like this, and how do you think it affected your writing?

KF: The biggest difference between EAT and a more conventional academic theater was that EAT focused on student-written plays. Sure, they would throw in an old chestnut—like A Raisin in the Sun or The Glass Menagerie—if they thought they had a fresh take, but pick a given season in its 21 years and chances are it’s dominated by productions written by students. This meant, too, that the emphasis was more on the script than it was on other production values. Readings were popular, which were not as prevalent in the Midwest as they are in places like New York (where scripts can sometimes be read to death), and rewriting was encouraged up until very late in the process, which wasn’t the most popular allowance with the actors. There were certain actors, directors, and crew members whose faces would quickly become very familiar to anyone who worked on more than one show. The table at an initial read-through was often filled with people you had probably worked with not three months before. It felt more like a community than a department.

I never actually took a playwriting class with any member of EAT, so it’s hard to say what I learned as a writer with them, not in any kind of pass-the-test kind of way. There was no textbook. There were no lectures, no exercises. Just a bunch of people who were hellbent on bringing a different kind of theater to Lawrence, Kansas.

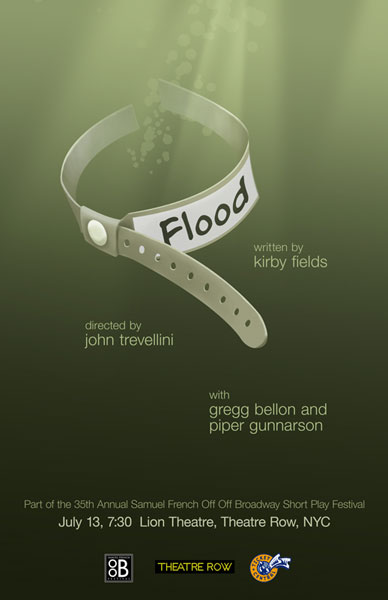

OOB: Talk about your entry to this year’s festival. How did you come to write this play? Was there a particular inspiration behind its creation? What do you hope festival audience will take from your play?

KF: I wrote the opening monologue to Flood in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, but I had no idea where it went from there. I had a vague notion that a man was going to take advantage of a natural disaster to serve his own gain, and I was pretty sure a baby was going to be involved, but the pieces just weren’t coming together (they seem so obvious now). I went on to other things, put the monologue away for four years.

During that time, my wife and I had a baby of our own, and the experience of being a father myself gave me everything I needed to flesh out the rest of the story. One night I ran into a roadblock with another play I had been working on for some time, so I idly opened the old file (“Flood Monologue”) in an effort to salvage the night. I read that first page again, and the rest of the play just flowed. I guess I could say that it took four years to write, though it was really only five nights stretched over all of that time.

OOB: What is the history of your festival entry? Do you plan to hone and further develop the play in upcoming rehearsals? Has it already been produced?

KF: I’m a founding member of a writers group that includes a handful of Carnegie Mellon ex-pats (“61A,” named in honor of the bus that took some of us from home to campus every day). We’ve been meeting twice a month for a couple of years now, and the first draft of Flood was workshopped with that group of trusted writers. I made some tweaks to the play based on their feedback, which is the version of the play that we will be taking into rehearsal. We’re writers, not actors, so I have no doubt that the play will go through further revisions once we get it on its feet. I find that actors sometimes know the rhythm of a line better when they speak it than I do when I write it. Revisions often follow. I’m looking forward to seeing what the process reveals.

OOB: Tell us a little about your producer? How did you come to form your relationship together?

KF: My producer on this project is another member of our writers group, John Trevellini. Trev is a proverbial jack-of-all-trades when it comes to theater. In addition to being a writer himself and the Technical Director for the Abingdon Theater, he has directed forNicu Spoon Theater and produced his own show (Boots) for the Fringe Festival. I haven’t connected with many producing companies in New York, so when it came time to submit Flood to the Samuel French Off Off Broadway Short Play Festival, I went to John and said, “If this gets in, you wanna do this?” As I expected, he gave an enthusiastic “Hell, yes.” I’ve known John for a number of years now. Our professional relationship has always been that of two writers. I’m excited to be working with him in this new capacity.

OOB: Looking back over your personal history in the theatre, what emerges as your favorite memory? Is there a particular story you’d like to share?

KF: Until he retired a couple of years ago, my dad was a theater professor and a director. My mom would always take us to see his shows, so from a very young age I was exposed to such plays as All My Sons, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Hot L Baltimore, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. I was too young to appreciate them fully, but looking back I’m not sure that was the point.

Looking back, I think the point was more that I was introduced to the ritual of regularly seeing theater. Eventually, we wouldn’t just go see his shows. We’d see whatever shows the department was doing at the time or whatever was coming through town and when we moved to a town where things didn’t really come through, we’d drive three hours to get our theater fix. We went to the theater more often than we went to church. I blame these experiences on why I find it difficult to come up with an anecdote that qualifies as a favorite memory. There have been so many. I don’t think it’s fair to have to choose.

OOB: Can you talk a little more about have a parent that worked as a theatre professional? How did growing up seeing shows come to influence your writing later? Are there particular plays or writers that have an influence over your work?

KF: The longest my dad taught anywhere was I-don’t-know-exactly-how-many-years in a smallish town in the Midwest. This town never claimed itself as any kind of a cultural center, and I don’t guess that anyone would ever make that claim on its behalf. In this way, the theater department at the college kind of functioned in opposition to the prevailing attitude of the rest of the community. Not long after we moved there—from San Diego, I suppose it’s worth mentioning—a director in a city about an hour away did a production of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart. Soon after the show opened, his house burned down. The relationship between the two did not seem to be coincidental. My dad played it safe with a few shows—Brighton Beach, comes to mind, and Black Comedy—but he also mounted productions of plays like Oleanna, Godspell, and, eventually, The Laramie Project. The area was a little more tolerant by then. People would write letters to the editor rather than setting houses on fire, which I took as a sign of progress.

I’m a sucker for a well told story, rich in characterization, but the playwrights I admire the most are the ones who could be accused of having a little subversive streak in them, playwrights like Suzan-Lori Parks or Tony Kushner or, yes, Mamet. What I most respect about them is that I don’t know that they sit down and say to themselves, “I’m going to write a subversive play” (OK, maybe Mamet does), but, rather, they write what they feel, and it just has a way of striking a chord.

To say that their writing has influenced mine would be presumptuous. Say, rather, that these are the kinds of writers who make me want to write.

Original Story Located Here

(Return to Top) |