Sit On Me When I Am Dead!

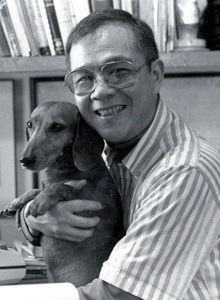

Although my brothers and I were born of Chinese parents in the Philippines, the three of us emigrated to the United States, separately and for totally different reasons, when we were all in our mid-twenties. It was in the United States where we all established our professional careers; where John and Peter met the wonderful women they married, had well-behaved children (two each) and saw them all graduate successfully from college; and where we will in all likelihood die and be buried—John and Vivian in New Jersey, Peter and Bing in Florida, and me in Kansas.

In life, we who teach and toil at the University of Kansas are paid only modestly, but one of our more attractive fringe benefits is that, when we finally drop dead, those of us who’ve put in time for at least fifteen years at the university, are entitled to be buried FOR FREE at Pioneer Cemetery, a grassy knoll owned and maintained by the university, situated between the five student dormitories on top of old Daisy Hill on Mount Oread, and the new development known as West Campus. Let me tell you about the bridge which connects the two campuses.

There’s a rumor that foot traffic on the bridge is busiest at night, when students living in the five dorms find themselves sneaking over to the secluded cemetery to indulge, first in alcoholic beverages and other controlled substances, and then, if they’re not too inebriated or stoned, to dangle their participles and split their infinitives, maybe even learn new ways of conjugating not just their verbs but also their nouns. That the life cycle gets reenacted nightly at Pioneer Cemetery, with the learned spirits of dead professors continuing to have a seminal effect on their young (dis)charges, is something which might give comfort to the aging faculty and staff at the university. Who needs Cinemax or the Playboy Channel in the afterlife when the frisky students are providing live entertainment for free? In truth, this is where many of my free-thinking friends and colleagues are buried—Ed Grier, Bud Hirsch—and this is where I too will be inurned, underneath a small rectangular slab of marble. In earlier, more promiscuous days, I thought my epitaph should read: “He finally sleeps alone.” But, these days, I think the Bard will get to have the final say: “The rest is silence.”

In the Philippines, the tradition among the Chinese is for entire generations of families to be buried together, if the clan can afford it, in elaborate mausoleums. The ones at the old Chinese Cemetery are truly ostentatious, outdoing each other in sheer red-and-gold garishness. The ones at the Manila Memorial Park are equally expansive and expensive, but in better taste, which means that you get more peace and tranquility by way of landscaping, and thus a lot less marble to house your loved ones. When my father died in December of 1969, eighteen months after I left Manila for the United States, my mother carefully studied the feng shui at the Manila Memorial Park before buying a double burial plot, one for my father, and the other for herself when her time comes.

I thought this was all settled until my brothers John and Peter decided otherwise. Since the three of us are now in the United States and will presumably be buried in the United States, they argued, shouldn’t our mother also be buried with us in America? But where? With John and Vivian in West Windsor? With Peter and Bing in Orlando? With me in Lawrence? The University of Kansas extends burial privileges at Pioneer Cemetery only to its employees and their spouses, no other beloved family members, not even pets.

Quite fortuitously, one year back in the mid-1990s, when my mother just happened to be visiting Peter and Bing in Orlando for Thanksgiving, John and Vivian and I all flew in to join them for the holiday weekend. Peter had done his homework, but we were all a bit apprehensive about how my mother would react to yet another discussion involving her own mortality. The Chinese are superstitious about these things. Peter assured us he would broach the subject subtly, casually. And so, while we were all out for a leisurely drive one afternoon, he said, “By the way, why don’t we all pop over to Woodlawn Memorial Park and Funeral Home? I have a friend who works there whom I’d like you to meet.”

We all expected Mommie Dearest to crackle and explode, maybe even to spontaneously combust, as she is wont to do on such occasions, but she surprised us when she smiled approvingly and said to Peter, “You have a friend who works on Sunday afternoons? What a hard-working boy! His mother must be very proud of him.”

Peter’s friend turned out to be a Latino who knew exactly how to flatter aging Chinese women. YOU! THE MOTHER OF THREE SONS? IMPOSSIBLE! SO YOUNG! SO BEAUTIFUL! SO RICH…IN BLESSINGS! He could have sold my mother a swamp full of crocodiles but, wait a minute, only if the feng shui was right, with gentle winds blowing from here to here, and soothing waters flowing from there to there. After what seemed like hours, mother finally found a spot which met with her “good feng shui seal of approval.” It was a corner lot on the corner of which was a scraggly weeping willow tree in desperate need of fertilizing. But there was another, more serious problem.

This particular corner lot had room for only FOUR coffin spaces. Mother said she would gather the bones of my father from his resting place at the Manila Memorial Park, and that these can be interred with her in one of the four spaces. My brother John and his wife Vivian said their particular branch of Protestantism forbids cremation, so they would need two of the four spaces. My brother Peter and his wife Bing said their religion has no special burial restrictions, so the both of them can be cremated and placed within the same space, the fourth and last available space on that corner lot.

So what about me and my dogs? Where’s our resting place in this developing subplot? The corner plot wasn’t cheap. After adding up all the hidden costs, the three Lim brothers would be splitting the bill equally, roughly $6,000 each. So what do I get for my $6,000? Peter’s friend shook his head gravely. And then he had a voila! moment. Sorry about mixing my metaphors, but I can’t think of what a voila! moment might sound like in Spanish.

“Oye! of little faith,” the man suddenly exclaimed. “Do you not see the beautiful weeping willow tree in the corner? Imagine a marble bench in that corner, underneath the tree. There can be as many as FOUR urns inside that bench! You can have the ashes of all your dogs with you inside that bench! Together, you will be guarding the final resting place of your loved ones! And all your friends and relatives can sit and rest on the bench as well, admiring the view, thinking only good thoughts of you and your family!”

“Gee, thanks,” I growled under my breath. “All my life I’ve wanted people to sit on me, and now I get to have my wish when I am dead!”

“Don’t be petulant,” my mother said, although there is no such word as “petulant” in Fukienese, the Chinese dialect that we speak. I was fighting a losing battle against her notions of feng shui. I could feel the wind blowing against my face, and it wasn’t fragrant. I could feel the blood flowing through my veins, and it wasn’t thicker than water. So what’s a dutiful Chinese son to do? I acquiesced, and spent the next couple of years sending in the monthly payments for my $6,000 bench.

Ultimately, I don’t know if it really makes any difference, after I’m dead, whether I’m inurned at Pioneer Cemetery in Lawrence, or at Woodlawn Memorial Park in Orlando. In one scenario, future generations will be fucking on top of me. In the other scenario, they will be sitting on me. In either case, purely for hygienic reasons, I hope they’re wearing clean underwear. Ay, caramba!